Over Christmas, I volunteered for Crisis at Christmas, a massive charity operation to feed and house homeless people in London over the Christmas period. It prompted predictably mixed feelings of guilt and pride, shame and satisfaction.

It’s easy to be cynical about this sort of thing – rich people who ignore homeless people for 360 days a year getting all righteous about being do-goody for a few hours, only to abandon the homeless again come new years. But this is a programme that has been running for over 40 years, and many of the long term volunteers are former guests – according to them, it works. Even if you do have blinkers for the homeless most of the time, volunteering in this way does help, and if it makes you feel good too, there’s no harm in that. Just as long as you don’t think the problem is solved when your shift ends.

Thinking big, really big

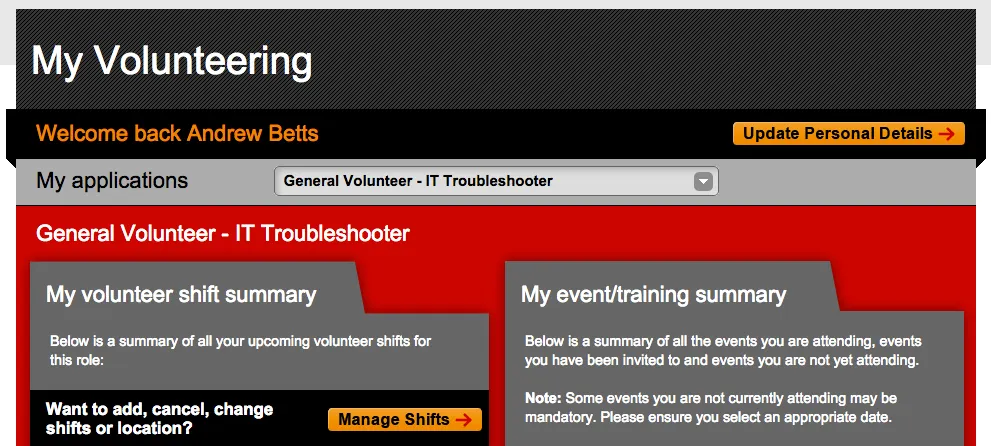

The logistics and ambition of the Crisis operation are pretty mind-blowing. Via a slick online system, 10,000 volunteers are recruited. You sign up for 8-10 hour shifts at one of the eleven locations across London, three of which are open 24 hours a day for the whole Christmas period. Those with special skills (medical qualifications, drivers licence, or fluency in foreign languages being the most sought-after) are flagged and allocated accordingly.

Sounds straightforward, but when it comes down to it, most volunteers are first timers who don’t have any experience doing shift work or working with vulnerable people. They’re not paid, and when the shift begins, the organisers simply trust that they’ll turn up. Each centre needs a hundred fresh volunteers every 8 hours to replenish the staff. Some just don’t show up, and being late is as good as not showing when you have an outgoing shift that needs to leave. I can’t begin to imagine the nerves of steel that must be required to be a shift leader for Crisis.

During this 2014 season, Crisis cared for 3,620 guests. Volunteers served 30,000 meals, and provided 656 healthcare consultations. According to the Homeless Link Winter Shelter list, most boroughs of London have small night shelters with a average capacity of around 15-30 people. In contrast, Crisis at Christmas can house 800 and provides far more than just a roof.

One stop shop

The centres (mine was in West London, I’m not allowed to say exactly where) offer a wide variety of services:

- Hair dressing

- Dentistry

- Optometry

- Arts and crafts

- Board games

- Films

- Hot meals

- Showers

- Dorms

- Housing advice

- Counselling

- Addiction support groups

- Internet access

General volunteers like me help provide some of the services, like the games, arts and crafts, serve food and maintain facilities like the showers and loos. Specialist volunteers provide the other services like advice and medical consultations. Coloured badges identify the volunteers by specialism and language so everyone knows where you can and cannot go, what you can and can’t do, and who you can talk to. I was designated an IT specialist so spent some of my time helping to keep the computers running smoothly.

There is no stereotype

There were a lot of surprises. One is just how varied the guests are. Without badges, it’s often hard to tell the difference between guests and volunteers (especially volunteers who’ve done a few night shifts in a row!). Many are extremely talented (I met painters, magicians, military veterans, even a chess master), most are friendly. Some are unpleasant, but then there were a few volunteers I didn’t like either.

Gap duty

Another surprise is the existence of something called gap duty and the discovery that it requires, at any one time, about half the entire volunteer staff. The buildings Crisis uses (ours was a school/college) are often large and full of areas the organisers are not using. Wherever there is a possibility of someone physically getting through from an area that’s in use to one that’s not, there are two volunteers, sitting on chairs, chatting to guests and making sure no-one crosses the gap.

In sleeping areas too, volunteers are stationed to sit quietly and simply watch people sleep. All this would seem like a lot of wasteful use of volunteer labour and paranoia, but for the fact that a guest said this to one of the volunteers on my shift when he woke up:

I wouldn’t sleep more than an hour, because I’m always afraid. But with you watching over me I sleep a whole night. No-one is going to touch me, or take my stuff. You’re my guardian angels.

Volunteers doing gap and sleeping duties are making the guests feel safe, and that’s probably the most important job of all.

Debrief

At the end of a shift, once the new shift have completed their briefing and been rotated into service, there’s a debrief for the outgoing shift. One of mine was the last night shift before the centre closed at the end of the season, and two guests had asked to come to the debrief session. One had come to Crisis homeless, had made contact with a son he hadn’t seen in a decade (which I helped him do in the Internet area!), and found somewhere to live. The other wrote us a poem which reduced a hundred people to tears.

So if it clearly works, and guests clearly appreciate it this much, and it’s an utterly trivial inconvenience for someone whose biggest recent housing problem was deciding which pillow to choose from a hotel’s pillow menu, then there’s no excuse for not doing it.

If you want to get involved, you can sign up to volunteer next year, or donate to sponsor a place.

The images in this post were taken and published by Crisis (who retain the copyright) with the permission of the guests pictured. Volunteers are not allowed to take photos in Crisis centres