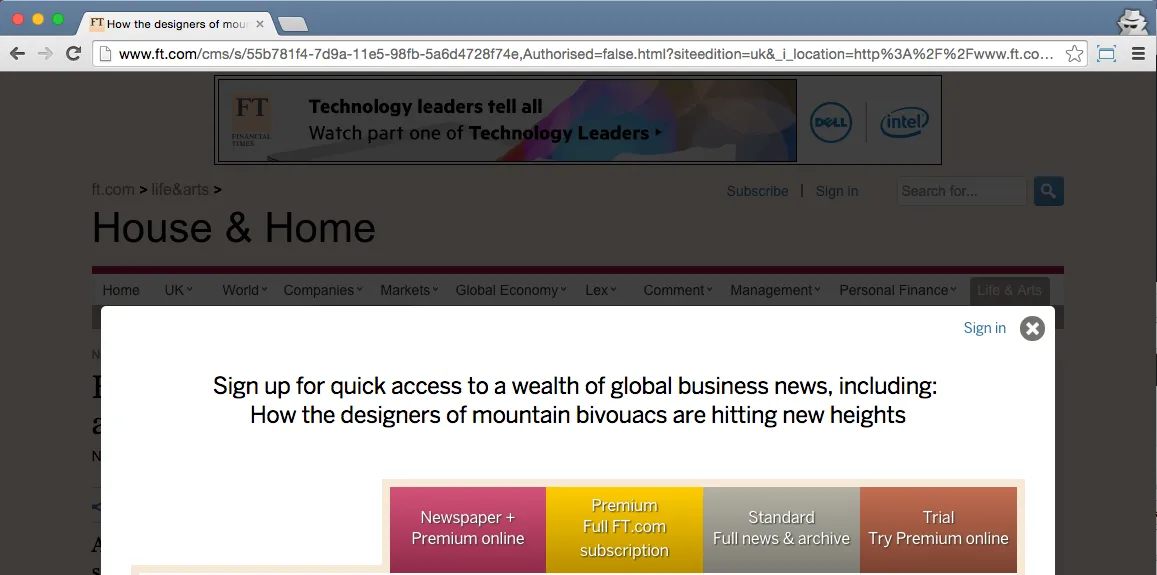

Paywalled news sites like the FT (where I work) typically allow search crawlers such as Googlebot to see premium content, but don’t want to allow everyone to see it for free otherwise we wouldn’t make any money. Search engines created first click free to demand a good experience for their users, but for lots of reasons, first click free sucks. Here’s a better solution.

First, let’s look at why First click free is so terrible:

- Sharing: In FCF world, sharing is a nightmare. Imagine two users who creatively I’m going to call Alice and Bob. Alice finds an article via search, and clicks on it. The publisher delivers the page free. Alice shares the URL with Bob by email, but when Bob clicks the link, he gets a paywall. We set up Alice with an expectation that her experience would be shared by Bob, but it wasn’t.

- Security: FCF is literally one of the most insecure technologies ever invented. I can exploit FCF to get around most paywalls in under 10 seconds. And yet the tech companies that advocate it are some of the most security conscious organisations on the planet. The reason they ignore this problem is presumably because the loss of revenue is not theirs. Imagine if you could get unlimited downloads from iTunes simply by setting a well known HTTP header.

- Business model: There are a practically infinite number of ways that publishers can adjust their paywall policy to get the most engagement from customers and convert the largest number of subscriptions. Maybe customers prefer to be able to read a short summary of any article for free? Maybe they prefer to get X full articles per day/week/month before having to decide whether to pay? Gradual engagement slope? Single-article micropayments? Publishers need to have the freedom to experiment with these and use data to figure out how to operate their business. FCF severely restricts this ability.

You need to pay, you want to pay

There is declining but unfortunately still significant cohort of people who think all content “wants to be free” or similar nonsense, as if a newspaper article is some kind of captive and ill-treated elephant or something. The reality is that unless you want the internet to be populated solely with clickbait, jokes, cats and Rick Astley, someone has to pay for decent content. Sending people to Syria, working undercover investigating illegal mistreatment of workers, analysing a seminal piece of economic theory, these things are dangerous or insanely expensive. Advertising does not, and cannot, fund this stuff – especially since the use of ad blockers is now so prevalent that on average 20% of UK internet users and 15% of US users have them installed, and ad blocking companies are ironically taking out adverts in the FT.

There’s an important aspect of behavioural economics to this too. If your friends get content for free, you feel it’s OK to get that content for free too. In fact you feel like a bit of a mug if you are paying for it. This is a very well documented phenomenon – similar to the effect of parking a nice car with a smashed wing mirror in a rough area. That car is shown to get broken into and vandalised far more quickly than if it were pristine.

So what are content passes?

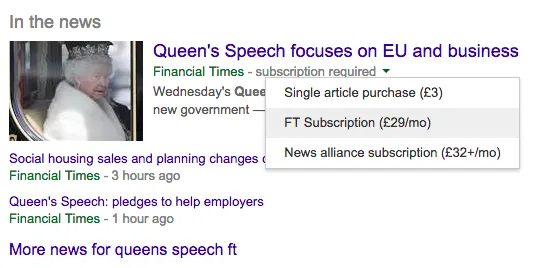

Content passes are a concept for a web standard that would offer an alternative to FCF. Instead of requiring a publisher to show premium content free of charge to a searcher, the search engine would require publishers of paywalled content to declare the paywall in the metadata of the article. The search engine can then surface that information to searchers before they click the link:

We start with the crawler visiting the article page. It gets the full content, but also sees this in the HEAD:

<link rel="contentpass" href="https://example.com/subscribe/monthly"/>

<link rel="contentpass" href="https://example.com/subscribe/buyarticle"/>The search engine now knows that if a user wants to see this article, they need to hold at least one of two content passes that are accepted by this publisher. The crawler then crawls the content pass URLs, and gets additional metadata about the pass:

<meta property="contentpass:name" content="FT Subscription"/>

<meta property="contentpass:payfreq" content="monthly"/>

<meta property="contentpass:price" content="29"/>

<meta property="contentpass:curr" content="GBP"/>

<meta property="contentpass:desc" content="Read unlimited articles from the FT for one monthly payment"/>End users visiting a content pass URL would get a signup form to purchase that pass, so the URL represents the pass both from a metadata and a functional perspective.

Everyone benefits

By exposing this data, publishers enable a lot of very sensible and user-friendly things:

- Ranking signals: A search engine could ask me (or determine heuristically) what content passes I own, and promote content that I have paid for higher up search results. This means that if I subscribe to the New Yorker but I don’t subscribe to The Times, the search engine will know to throw up New Yorker articles with a higher priority.

- Blocking: Conversely, if I know that I will never subscribe to some publication because it is super expensive, I could tell the search engine to suppress all content that requires the really expensive pass.

- Packages: In the TV world, it’s been common for years to have a bundle of channels in a package that you pay for with one payment. Content passes enable this to happen for digital content – I might not want to subscribe to the FT on its own, but if it comes in a package with the Wall St Journal and Bloomberg that might be a combo that works well for me.

In summary, search engines benefit because they gain new ground on which to compete with each other, and publishers benefit because we can sell our content more securely and experiment with lots of new products, offers and business models. Customers benefit from clarity, consistency of experience, fairness, and lower prices that would result from removing loopholes and increasing packaging and bundling of multiple publications into a single product.