I didn’t start out as strongly anti-AMP. Providing tools for making websites faster is always great, as is supporting users in developing countries with lighter-weight pages that don’t cost them a month’s wages. It’s totally true that today webpages are in a pretty sorry state.

Recently Google hosted an AMP conference, and to their credit invited critical voices to be on a panel to discuss concerns. Here’s the video:

Jeremy Keith’s and Tim Kadlec’s write-ups of this panel are spot on, and there are concerns here both with AMP as a format and with the use of AMP in Google search as a platform for content. My biggest concern is in the second category.

Devaluing credibility, destroying trust

When I saw this, I found it terrifying.

I tapped a link in the Twitter app, which showed as google.co.uk/amp/s/www.rt.c..., got a page in Twitter’s in-app webview, where the visible URL bar displays the reassuring 🔒 google.co.uk. But this is actually content from Russia Today, an organisation 100% funded by the Russian government and classified as propaganda by Columbia Journalism Review and by the former US Secretary of State. Google are allowing RT to get away with zero branding, and are happily distributing the content to a mass audience.

This is not OK. This is catastrophic.

Other problems

Ambiguous content attribution at scale is a scary thing indeed, but beyond the negative effect that AMP, and other distributed content systems, have on the authenticity of independent journalism, there are other significant issues too. Googlers like to consider AMP-the-format and AMP-the-platform separately, and while I think they are inseparable as concerns let’s look at the problems with each independently:

Issues with the format

- AMP pages prohibit

<script>

No script means (for the most part) no interactives, no menus, no share overlays, no saving, gifting, or sharing, no expanding content, no cart or tool integration, no comments. Sometimes AMP provides alternatives, but the ability for publishers to design their own UX is reduced. Less differentiation = less competition = lower revenue. - Centralisation of third party vendors

In the documentation for AMP analytics 90% of the words describe how to integrate with Google Analytics. Yes, you can also useamp-analyticsto integrate with, say, Adobe’s SiteCatalyst, but Adobe’s advice suggests using amp-iframe instead. amp-ad has a similar problem, with a whitelist of ad networks that it supports. This is a problem if you use one that’s not on this list (for example if you have your own in-house solution). The project is good at accepting submissions for new vendors, but it sets up a barrier to entry and a class system – Google is first class, other known vendors are second, everyone else is last. - It’s not always faster

For well built, modern, well optimised web pages with good user experience like The Guardian or the FT, the AMP page can actually load more slowly than our own pages, from a cold cache (the FT just won an industry award for fastest site).

Issues with the ‘top stories’ AMP platform

- Navigation is between sites, not within sites.

When you tap a result from Google’s ‘top stories’ carousel, you get an article page. Swipe left or right and AMP will usually take you to a story from a different publisher. Publishers are therefore left with scant opportunity to deeply engage the user, and readers are encouraged to ‘sample’ multiple sites without making a commitment to any particular one. That commitment is essential to cultivate an audience of paid subscribers, and FT’s internal data shows that onward journeys from AMP pages are much less likely than from our normal pages. - It recklessly devalues the URL

There are now so many URLs shared online with a visible part that does not include the publisher’s domain. www.google.co.uk/amp/s/ww… is not telling me anything about who published the content I will read. AMP also leads to multiple URLs that describe the same piece of content, something that will only get worse as more AMP caches are created.

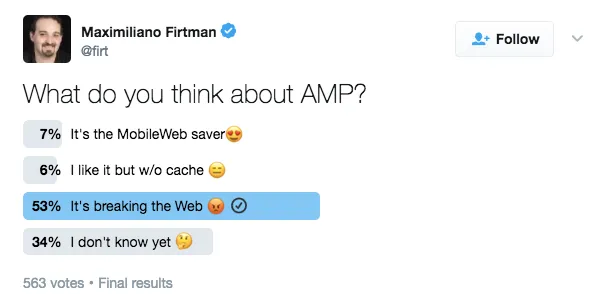

There is more, but in summary, AMP forces technical restrictions on publishers that limit their ability to create value for their customers, limit their ability to further engage the user beyond reading the initial article, and prevent them iterating on their business model with the freedom they would normally have. Added to this AMP may not actually be any faster than the publisher’s own webpages. And beyond Jeremy and Tim, there are many others who agree:

Creative marketing

Technical issues aside, AMP is also guilty of some very creative marketing which I find somewhat distasteful. For example, the idea that publishers can be more profitable with AMP pages is claim supported only with testimonials and case studies, with which (as any academic will tell you) you can prove anything (such as that chocolate cures skin wrinkles). But actual studies of decent amounts of data, carried out by the industry association Digital Content Next, show that AMP and similar platforms do not make more money (though I recognise industry associations are obviously not unbiased, there’s no reason for DCN to have a desired outcome here one way or the other).

There’s also the idea that AMP is ‘not a Google project’. The `.org` domain name, the branding (no Google logos), the accepting of contributions from non-Googlers… But the core contributors are all paid Google employees, Google hosts the projects, Google organised the AMP conference, it’s Google’s search that is most aggressively pushing the adoption of AMP, and all AMP’s third party integrations support Google’s own products (like analytics and ads). It’s as much a Google product as the Chrome web browser is.

Paul Bakaus and I have had discussions about AMP before, and I’ve taken issue with his debunking of supposed myths about AMP – because almost all of these ‘myths’ he attempts to debunk are actually not myths. At least to some extent, AMP is restricting layout options, it is about mobile, it is a Google project, and for publishers, adopting it is mostly about getting into the top stories carousel (which Gina Trapani also highlighted in the panel discussion embedded above)

Finally, the claim that AMP provides a way for Google to determine reliably whether a page is fast doesn’t ring true to me. Google has said for years that they use the speed of page loading as a ranking signal. Fast pages are already ranked higher than slow pages in search. AMP might make speed easier to verify, but it seems an extraordinary burden to force on the publishing industry just to save Google some machine learning work (which they’re historically very good at anyway)

All this makes AMP particularly frustrating because it surely persuades many developers that it is a better solution than Facebook’s instant articles or Apple News. If it is better, it is only marginally so, and the fundamental idea is basically the same. No need to take my word for this. Publishers almost universally group Instant articles, AMP and Apple news into the same category of their publishing strategy – most call it ‘distributed content’ (the term used in the very first sentence of the Reuters Digital News report, and also internally at the FT).

It’s hard to avoid the idea that the primary objective of AMP is really about hosting publisher content inside the Google ecosystem (as is more obviously the objective of Facebook Instant Articles and Apple News).

Media failings

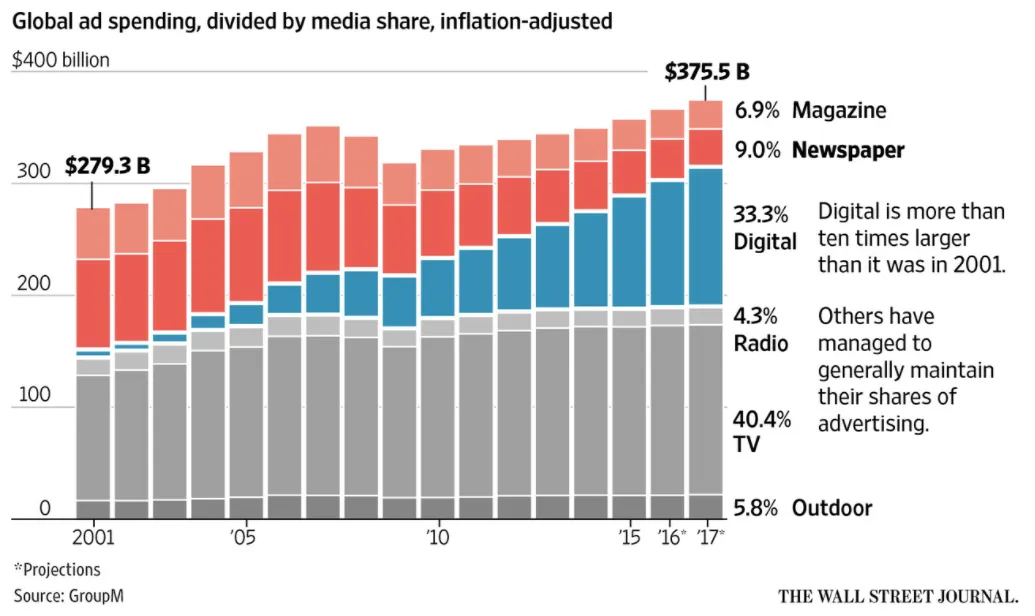

For all this, the biggest villain here is not Google or their well-meaning AMP team, it is the media industry for going along with it. The media have now almost completely lost control of distribution (one of the primary conclusions of last year’s Reuters Digital News report). When do we finally recognise that we can’t continue the fierce competition that has characterised the media of the 20th century, when the very existence of an independent media is under severe threat?

Technology companies are already surprisingly good at collaborating on things that drive forward their common agenda. Google is exceptionally good at it. Media companies need to be far better at this, figure out a distribution strategy that works, and wrestle it back from platforms that care more about amplifying popularity than establishing truth.

C’mon, what’s the worst that could happen?

So that brings us back to Russia Today.

Truth and evidence and nuance are hard to find, hard to represent accurately and fairly, expensive to distill into a consumable product, and hard to understand quickly. If the world’s biggest content discovery and delivery platforms prioritise security, performance and popularity, over authenticity, evidence and independence, well, the likely result is an exponential rise of simplistic, populistic thinking, inevitably spreading and amplifying until false beliefs become tacitly accepted as facts.

On the phone with Facebook PR and they literally ask me “what is truth”

— Nellie Bowles (@NellieBowles) November 15, 2016

When I imagine a Maslow’s pyramid of needs in relation to news, I think the need for truth is more important than the need for speed. Delivering propaganda faster is lovely if your customers want propaganda, and you are comfortable with being a provider of propaganda. But if you care about what you’re saying as well as how you’re saying it, then surfacing (and indeed cultivating) the right content should be far more important than firing out gibberish quickly.

My TAG colleague and inventor of the Web Tim Berners-Lee recently started more strongly pressing for action on fake news. This is hard, and in comparison, relying on popularity is easy.

Popularity is fine for filtering objective data, like a StackOverflow answer (which can usually be academically assessed as right or wrong), “good enough” for subjective opinions where there is a common goal, like restaurant reviews, and abjectly terrible for subjective opinions where goals are diametrically opposed, as is the case in politics.

It’s now evidently become so bad that a country of 300 million people, largely by algorithm-fuelled populism, were persuaded to elect someone whose policy agenda is objectively beneficial to only a tiny, elite fraction of the electorate, and to a foreign power, as President of the United States. Google, Facebook and Trump all became winners by amplifying and trading on what’s popular. Now we have seen the result of this populism play out twice electorally in the space of a year, starting with the UK’s decision to leave the European Union.

How this can be fixed

It’s not all bad news. Advertisers are reportedly starting to boycott YouTube for fear of their brand being associated with videos espousing political extremism. And there are signs that this is starting to convince platforms to do something about it – such as Facebook’s recent efforts to flag stories as ‘disputed’ when appropriate, though their approach is hilariously conservative when compared with the damage they are causing by not doing something drastically stronger.

If you want an independent news industry that produces quality, accurate, accessible content, we need to incentivise accuracy, not virality, and maintain creator-control over distribution. For AMP’s part, this means:

- Don’t prioritise speed over accuracy by giving overwhelming ranking preference to content published as AMP

- Don’t prevent publishers from differentiating their content by prohibiting content creators from using standard web technologies

- Don’t devalue the origin model and trust relationship with domains by repurposing others’ content within your own ecosystem. This also annexes control, traffic and crucial revenue from content creators.

And at the same time, we need a much stronger focus on authenticity as a strong ranking signal. This is not only critical to avoid potentially huge societal implications of bad decision making, but also cultivates better content by improving incentives for creators.

If we continue inventing new ways to incentivise propaganda, this will be how liberty dies: with thunderous applause. And distributed content.

Notes:

- The concerns expressed here apply equally, if not more so, to Facebook and Apple, but were prompted by the recent AMP Conference.

- While RT is widely considered a disreputable news source, the article included in this post describes a true story. It was also reported widely by other outlets such as Reuters