Life moved on and there was never an Edge conf 6, but some of the things we pioneered have inspired other events. This post is the long-overdue Edge conf playbook.

I’d been to a lot of developer events prior to starting Edge, and the following are common problems with them:

- Speakers are boring: I know this because I’ve been a boring speaker. I could see people in the audience who are writing way too much code to be paying attention. Speakers are often not trained, and with this being 1 communication, it’s hard to please everyone in the room.

- Talks are black boxes: I get unbelievably frustrated with talk titles like “The new black” or “Living dangerously”. Stop trying to write tabloid headlines and tell me what the talk is actually about. This also makes it hard to tell if the talk is there because it’s genuinely interesting or because the speaker’s company is a sponsor.

- There’s no level-setting: When I go to a talk on web security as someone with a moderate existing knowledge and get 40 minutes of SQL injection examples, I feel like I wasted my time.

- Q&A is awful: Public Q&A sessions are structured with terrible incentives, specifically they incentivise people who seek attention to spend as much time as possible asking a question no-one wants to know the answer to, or which just doesn’t make any sense. There is no filter on spontaneous Q&A.

- The breaks are the best bit: Often it’s just having the opportunity to be in the same place as people you want to network with that leads to the most interesting conversations.

- Attendee knowledge is not surfaced: We like to pretend that the speakers are ‘rockstars’ and attendees are there to bask in their reflected glory. This tacitly endorses and perpetuates a class system that errects barriers against new entrants. A lot of attendees have stuff to share, sometimes they just need to be given a platform and the assurance that there is no pedestal and the invited speakers are not holier than thou.

In trying to fix these perceived issues, I made a lot of mistakes, and iterated, but over five events we got a good handle on what was working. This is the playbook, and I’d love to see more events doing some of this stuff.

Panels, but better

Panels are almost always awful. “Let’s just go down the line and say a few words about ourselves” – and half an hour of everyone’s life is duly destroyed. But panels are great if run well. Disagreement can surface, genuinely new ideas can suddenly emerge, and everyone can come away energised. Here’s how to do it:

- Choose a moderator for their social skills first, and knowledge of the subject second

- Seat the moderator in the middle of the panel, with the rest of the panellists in an arc around them. All panellists must be able to see each other and the moderator.

- Use comfortable chairs with back support, provide water and a coffee table within easy reach of each panellist

- The day before the conference, train all the moderators in the actual space. Do role play. Teach good moderation patterns, including how to use effective debating techniques. Write a moderation handbook for moderators to study the day before, and put a cheatsheet with the key points in front of them during the session.

- Position a timekeeper in the front row to signal the moderator when they should change topic to keep things moving. Use simple flash cards. Don’t allow them to dwell on something for too long, but don’t make it the moderator’s problem to do timekeeping either. They have better things to do.

- Put headshots of the panel on a big screen behind them, facing the audience,in the same physical layout as the panel is seated, so it’s easy to refer to the screen to see who they are. Then cut down introductions to 10 seconds each.

- Put quieter members of the panel next to the moderator. People who need less prompting to speak can go on the wings.

Chat channel

We were the first event I’m aware of to have a slack team for all attendees to join, and we had an order of magnitude more engagement with it than I’ve seen at any event since. At Edge 5, 200 attendees sent over 6,000 messages during just 4 panel sessions.

This is basically the @edgeconf slack: https://t.co/IWX7GGj07W (in that it’s insanely fast!)

— @rem (@rem) June 27, 2015

Here’s how to make chat engaging:

- Make sure everyone registers. We required registration on Slack to do anything at the conference, and we pre-invited everyone. Attendees would also not be invited back to the next conference unless they logged into Slack at least once.

- Have a channel per session, and a lobby channel where the session channels are promoted when their sessions begin

- Inject important information into the channel, like who is currently speaking.

- Put the slack channel on a monitor facing the moderator and ask them to refer to it regularly: “I see on slack we have some discussion about…”

- Plant stuff – prearrange with some confident attendees to have some opinions up their sleeve to put on the chat, so that less confident people don’t have to break the ice themselves

- Have a chat moderator. Someone on the event staff should be in the session channel to introduce the session in text, similarly to what the live moderator is doing on the stage, encourage participation, reassure attendees that DMs are open for any CoC concerns.

- Require real names and photos. There are good reasons for anonymity online, but in a physical event, assuming you don’t have a paper bag over your head, we can see you, so it’s useful to be able to match chat participants with the people you can see around you.

- Use a clear avatar ribbon or watermark to indicate which chat participants are event staff, and add phone numbers to their profiles.

Crowdsourced questions

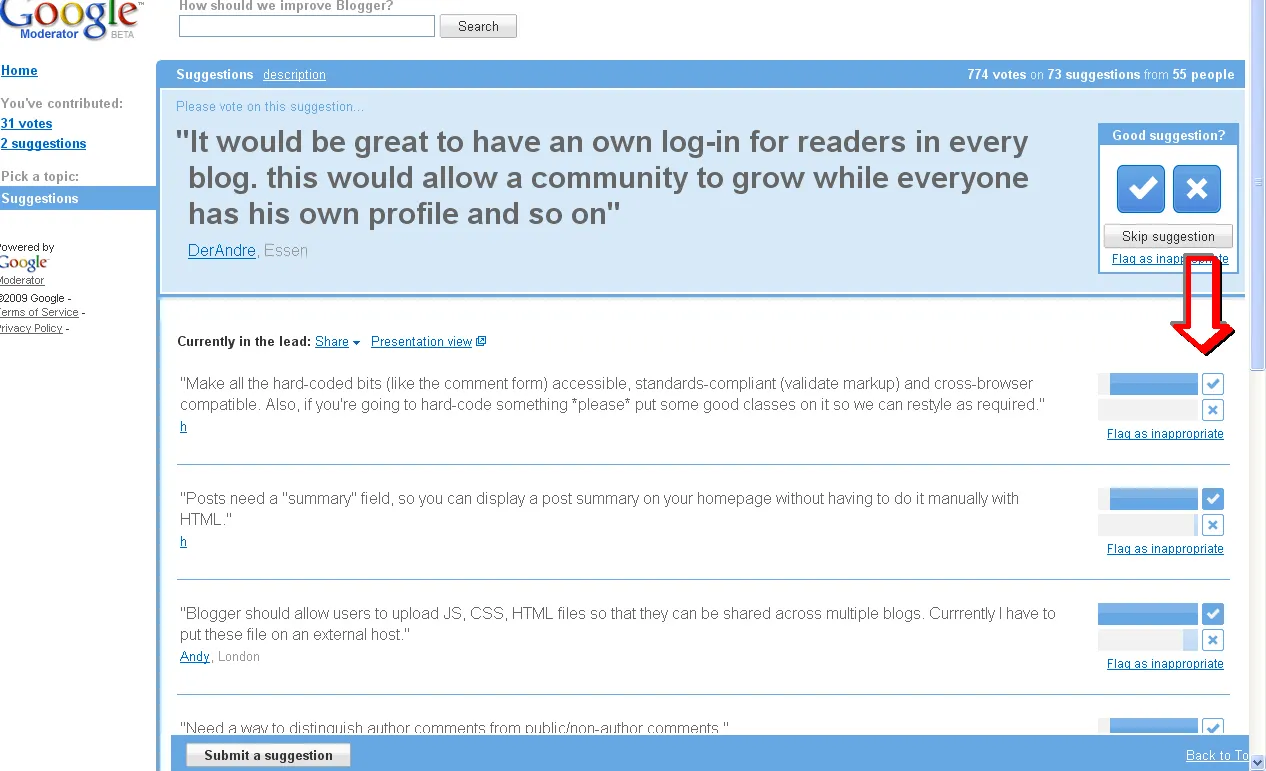

Try to figure out what the session will discuss before the event starts. We did this with Google Moderator, which sadly doesn’t exist anymore. We got dozens of question suggestions for each session, shortlisted seven, and told all the panellists what they were the night before the event (but asked the panellists not to discuss the topics between themselves until the session).

By doing this, you totally avoid unfiltered Q&A, and keep the quality high. You can allocate a fixed amount of time to each question, and know what the agenda for the session is. Put the current question under discussion on the big screen (Daytime-talkshow-style!) so everyone knows what the constraints are for any intervention they might make.

We tried getting the original author to ask the question, but we’d often rewrite it, so they turned out to be uncomfortable doing that (One questioner at Edge 2 said “This is an anonymous question” before asking the question we’d given him, and then everyone did that, which was distracting). Get the moderator to ask the questions.

Attendee opinions

We didn’t want unfiltered Q&A, but we also didn’t want the audience to be passive. In fact, we wanted the attendees to be contributing primary content to the session. Here’s how to do that:

- When registering for the conference, ask attendees to tick a box to say they are intending to contribute to sessions. Make it clear up front that we expect everyone to get involved, not just listen

- When attendees post useful contributions in chat, have a chat moderator encourage them to voice that opinion for the room (this also validates for them that their point is worthy of being voiced)

- If attendees choose not to voice their useful contribution, the live panel moderator can pick the point off the chat and raise it themselves, crediting the author

- Use a tool to enable attendees to ‘raise their hand’ without doing so physically. Raising and keeping your hand in the air is actually really physically tough to do, and for some more than others. We used a chatbot, which also allowed us to maintain a ‘queue’ of people who wanted to speak and automatically prioritise those who had spoken least.

- When audience members speak, make them as important as the panellists by displaying their name and affiliation in real time on the big screen or in the chat channel. This is easy to do if you have a digital queue and all the attendees have registered with it, like they did with our Slack bot.

- Have the moderator throw to audience speakers several at a time, and then go back to the panel while the microphones are being deployed. Never, ever, keep the whole room waiting while microphones are sent around. This destroys the energy in the room instantly.

- Take several audience points before returning to the panel. This gives maximum opportunity for attendees to participate, and avoids distracting the session by having to spend time discussing a single less-interesting opinion.

People who didn’t come to #edgeconf have made a huge mistake…

— Mark Nottingham (@mnot) September 20, 2014

Robots

We gradually did more and more with chatbots, and they are awesome. Try these ideas:

- Pre-canned messages to go out at the right times to annouce session locations, start times, and to remind attendees of CoC

- Allow attendees to use a chatbot command to:

- raise their hand in a session

- give conference feedback

- register for a breakout

- express real time sentiment (good contribution / bad contribution) about any current speaker (anonymised and aggregated)

- order coffee (we didn’t actually do this but John Alsopp does it at Web Directions and it is a literally genius idea that I wish I’d thought of first)

Breakouts

We didn’t just do panels. We ended up gradually giving more emphasis to breakout sessions, which would follow the panels, but these were also meticulously planned:

- Nominate a host and a scribe for each session

- Provide stationery: flipchart, whiteboards, markers, post-its etc.

- Give the host a “breakout pack” with an example structure, as well as some ice breaker exercises they could do. For example, we printed pairs of cards, some just with colours, and some with CSS colour names, and attendees spent 5 minutes at the start of the session trying to pair them up!

- Stipulate that at the end of the session, the host needs to summarise conclusions in 30 seconds. This will focus the mind on achieving a deliverable.

Having the traditional #EdgeConf problem: can’t decide which great session to go to.

— Alex Russell (@slightlylate) June 27, 2015

Vetting & streaming

One problem with ‘conventional’ events is that literally anyone can go. That sounds dangrously elitist, but I have personal experience of several kinds of attendee that devalue conferences and disrespect the work that organisers put into creating events:

- People who are there because their normal job is less interesting and they can expense the ticket, but they’re not interested in actually learning or sharing anything.

- People who are not developers. Recruiters are the obvious culprits, and I’ve been to several sell-out events where genuine attendees could have come, had there not been recruiters blocking their seats.

- People who buy tickets and then don’t turn up at all.

For Edge, I decided to ask all attendees to apply for a ticket. They were asked for a short proposal, part of confirming that they possess some engineering expertise, are willing to share it, and have specific things they are interested in learning. We then vetted these in an anonymised process, and prioritised ticket sales based on that.

Oh my goodness. There are some seriously clever people here. #EdgeConf

— Kristina Auckland (@kaelifa) February 9, 2013

(…including her)

Anyone that passed vetting and bought a ticket but didn’t use it (and didn’t cancel), automatically failed vetting if they applied for a ticket for the next event.

Our attendance rate at Edge 1 was 98.2%. It stayed ludicrously high through all Edge events (except Edge 4, for some reason).

To balance the slightly higher bar to come to the event, we streamed the entire event for free, live. So if you couldn’t or didn’t want to contribute, you could still consume the content as well as if you were there in person, but you weren’t blocking a seat that could be used by someone who would actively contribute. Obviously this is a costly thing to do, and we were very lucky to have good hosts who had the necessary equipment and generously provided in-house expertise.

It’s hard to follow the discussions while being sick, but watching the #edgeconf live-streamed while lying down on bed is priceless.

— Tomomi (TPE✈️SFO) (@girlie_mac) September 20, 2014

Physical exercise

Many people tune out when they are not physically active. In panels, we used catchbox microphones, which I love, and literally threw them at attendees. In breakouts, several of our ice breaker exercises encouraged some physical movement too.

Whilst being sensitive to some attendees’ inability to participate in this kind of thing, encouraging physical movement is a very good way to keep energy high.

Incentives

People need incentives to participate, especially cynical developers like me who reflexively click “NO” on every offer they ever receive! We got sponsors to donate prizes, and awarded them for:

- most contributions in a panel session from an attendee

- best contribution from an attendee

- most positively-received contribution

- random prize draw for anyone who submitted feedback

We also gave anyone who spoke up in a panel session an automatic pass to the next event, allowing them to bypass vetting.

Circular tables or other ‘irregular’ seating

For our panel sessions, we didn’t have space for round tables, but it is hard to overstate what a difference this makes. Rows of chairs tell people to sit down and be quiet. Use round tables instead if you can. We did it for the breakouts, and John does it at Web Directions even for the big keynotes. Round tables facilitate introductions and conversation.

I love that it feels like we’re all having a nice chat @edgeconf

— Kristina Auckland (@kaelifa) February 9, 2013

At Edge 1, we had trendy ‘assorted’ seating, a ramshackle assortment of meeting chairs, sofas, benches, bean bags, packing crates, virtually anything that you coud conceivably sit on. This meant that first, although everyone was roughly facing the stage, they were irregular enough that they mingled a lot, and second, since there was a big difference in comfort level between the types of seating, people naturally moved around during the day to allow everyone a chance to sit on the comfy sofas!

Blind matchmaking

I never managed to code this in time, but I really wanted to add a chatbot that would act as an intermediary in a conversation with another attendee, so you would invoke it, say what you were interested in, and you’d be connected with another attendee anonymously and given a topic to discuss. You’d be prohibited from revealing your identity or any demographic information about yourself, but you’d have the option to be revealed to each other at the end of the event.

I wondered whether this would challenge people’s understanding of others’ expertise and allow them freedom from any biases, consious or otherwise. The bot would try and spot obvious accidental use of gendered pronouns and strip them. I wonder how effective that might be.

Staying nimble and responsive

Plans go wrong, people are unpredictable, and you need to adapt. At Edge 5, we were hosted by Facebook, and their office air conditioning broke down (the facilities were otherwise outstanding). The temperature in the main space and some of the breakout rooms exceeded 30C by the afternoon.

We fretted, we waited, the engineers said it was fixed. It wasn’t. We ordered in industrial fans. They were too noisy and didn’t help.

Finally we decided that we’d just circle the block, buy every ice cream and ice lolly in all the local supermarkets, and give everyone ice cream to have during the breakouts. This response became the thing that was most positively reviewed by attendees from the whole day, and was a totally unplanned solution. People were hot and stressed and they reacted with great patience and kindness to the organisers, and were rewarded with ice cream! (or non-dairy lollies)

Being given ice cream to help us cope in the sweltering heat at #edgeconf nice one :)

— Adam Onishi (@onishiweb) June 27, 2015

Conclusions

All this sounds like an obsessive compulsive’s heaven, and to be honest, I am OCD and this event was an absolute expression of that. But with all the stress and anxiety that comes from obsessing over everything, it’s nice to be able to channel this instinct into something that achieves a measurable improvement in how we do stuff. Not everyone thinks that all of these things actually make a positive impact, but enough people seemed to that we kept going.

@sgalineau @nolanlawson @ryosukeniwa perhaps. I came away from Edgeconf with a TODO list for myself & to push for others internally.

— Jake Archibald (@jaffathecake) July 10, 2015

Really enjoyed the format of @edgeconf. Interesting conference, would attend again!

— Margaret Leibovic (@mleibovic) September 21, 2014

I may have been responsible for dreaming up all these ways of making running an event harder, but the only reason any of them actually worked was the indulgence, enthusiasm and hard work of my co-organisers. These people made Edge, and they sweated the details as much as I did. I’ve never thanked them enough and the following people in particular deserve more thanks:

- The team at FT: Rowan, Gallal, Luke, Alberto, Sam, Rob, Tim and other colleagues who got press ganged into time keeping, chat moderation, wayfinding, A/V liaison and scribing.

- Ruth Yarnit, event manager and director of White October events, and her colleague Vicky, ran event management for Edge 4 and 5 with a level of finesse I would never have achieved.

- Perry Dyball, my co-chair of London Web Performance, which ended up being the entity that ran the conference from a legal perspective.

- Torben Förster, who was an enthusiastic attendee of Edge 1, ended up helping me curate panellists, and run and maintain the website

- Wesley Hales developed a real time voting tool called OnSlyde that I reimagined as a live panel moderation tool, and, outstanding human that he is, he actually implemented all the stuff I asked for!

- All the wonderful experts and moderators who were willing to subject themselves to our experiments and sit on Edge conf panels.

I don’t know if there’ll be any more Edge conferences. I’d have to change the name for a start (thanks Microsoft, Akamai, IBM, Fastly!), but I’m actually more excited about seeing some of these ideas spread to other events. Especially if I can attend them without having to worry about being the one whose fault the whole thing is.