While developers celebrate hard-won interoperability and availability of better and better tools, a new front is opening with browsers increasingly appearing in unconventional devices, and these browsers… aren’t very good. The W3C’s Technical Architecture group has issued a finding to try and encourage better practice.

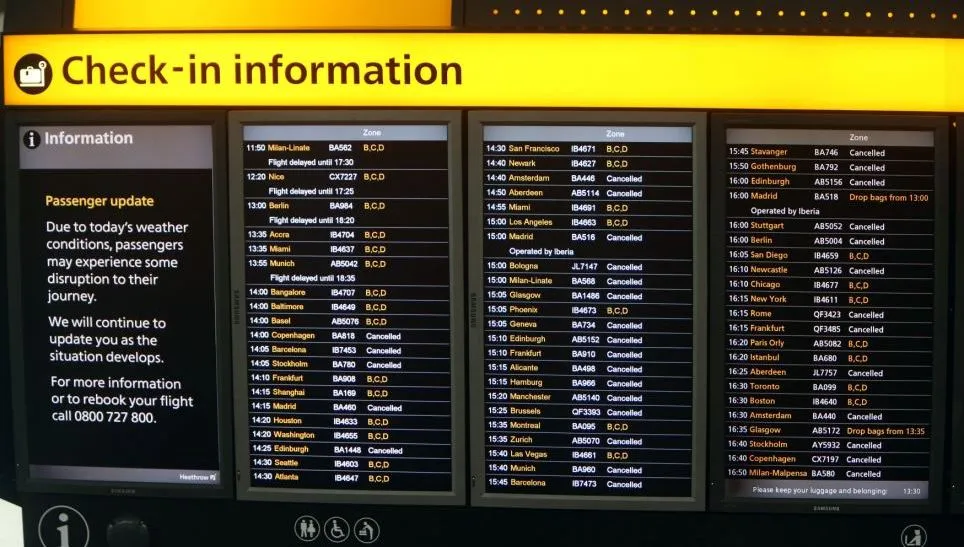

When I think of what devices I use that have a web browser, I imagine my laptop (which I’m using right now to write this), and my smartphone. But actually there are far more browsers in my life than this, and I just don’t realise it. My TV’s electronic programme guide may not seem like a web browser, but it’s using web technologies under the hood. Similarly, when I travel, the overhead screens at the airport that tell me which gate my flight is leaving from – those are often web browsers too. And once on the plane, the in-flight entertainment system is as likely as not also a web browser.

This isn’t in itself a problem. Web browsers are fantastic, some of the most secure, robust, highly tuned engines for displaying myriad forms of content with unparallelled compatibility across numerous platforms. It’s an obvious choice to use web technologies for all sorts of interface and information display applications.

Imagine you’re a car manufacturer and you chose to use web technologies and a browser for your in-car entertainment/navigation system UI. You’ve done all the hard work to get a browser in your car, so why not get a quick win by exposing it to the user – which allows you to market it as a feature of the product: it can browse the web too!

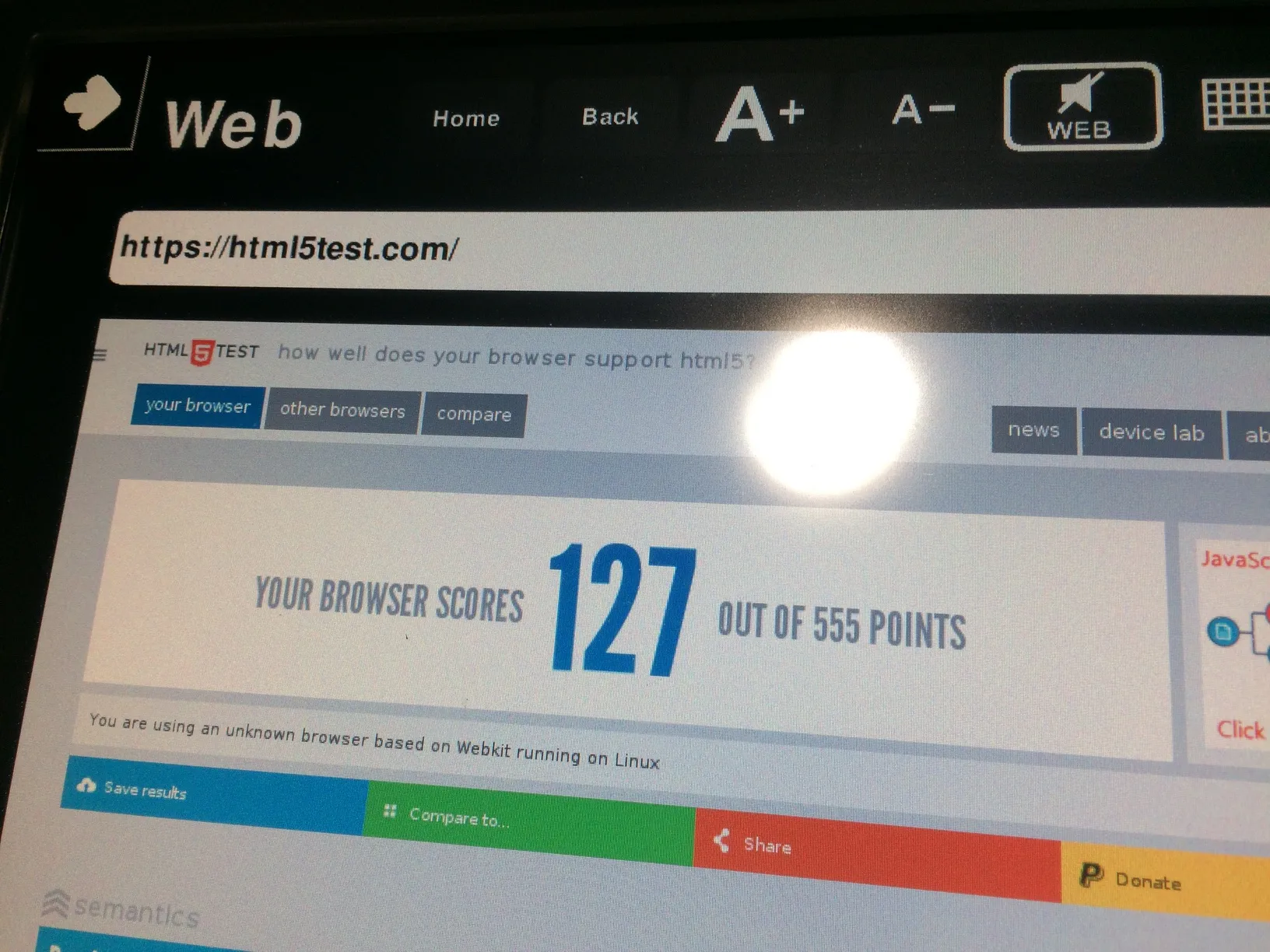

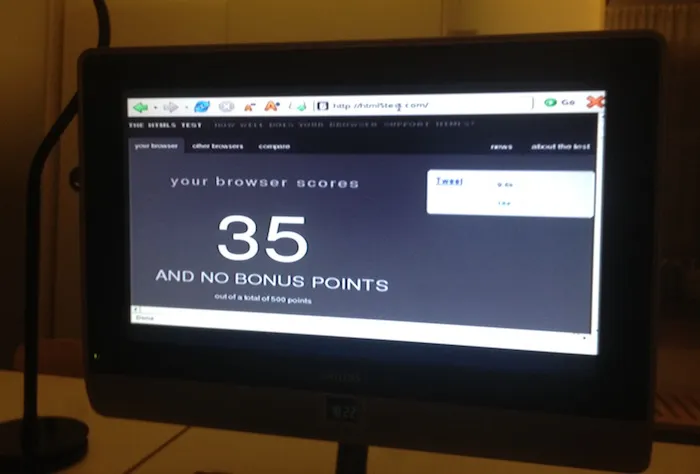

This is where the problems begin. There’s a world of difference between what you need in your browser to support the specific web technologies you plan on using in your own application, and what you need to display any site on the web that the user might choose to visit.

This kind of thing is potentially going to get worse. The web’s rate of evolution is punishing for many manufacturers to keep up with, and with more and more powerful features coming to the platform, it’s understandable that some manufacturers of low-power devices are looking to create a standard subset of those features, a kind of ‘web lite’.

This immediately prompts questions about what happens when the ‘real’ web adds more features. Does the subset automatically include them? In that case the subset is effectively a blacklist of web features that are intentionally unsupported for some reason. But more worryingly, the subset could be a comprehensive and alternative definition of what the web is – a whitelist of features that are supported. In that case, not only would it become increasingly stale and out of date as the real web adds new features that would not be part of the subset, but it could also itself evolve in a different direction, resulting in more than one World Wide Web.

The W3C’s Technical Architecture Group (of which I am a member) recently published a finding on The Evergreen Web, in which we caution against both subsetting the Web’s collection of standards, and also against distributing browser software that you have no intention to update (or worse, not even a mechanism for updating it).

The manufacturer’s dilemma

It’s understandable that this is a hard problem for manufacturers to solve, for a number of reasons:

- Some products have no built in networking capability (eg. car, treadmill), leaving it down to the end user to connect them to the Internet. Of course if they are not connected to the Internet they can’t browse the Web so this is both a problem and a solution, but it means update mechanisms must be prepared to fire up opportunistically and must be capable of leapfrogging dozens of versions in a single update.

- Many IoT devices have a very long lifetime. You keep your car longer than you keep your phone. A phone as old as many cars on the road today would not be updatable any more, because it costs too much to support every iteration of the hardware, plus new features may simply not run on the outdated architecture.

- Many manufacturers don’t own the drivers for the chips in their products. They buy systems-on-chips and drivers from a supplier, and they are then reliant on that supplier issuing updates to their drivers to support running new features on them. If the chip manufacturer drops support, there’s not much the product manufacturer can do about it.

- Manufacturers have very small browser teams, maybe 2-3 people working on their embedded browser, compared with the hundreds of world class engineers that work on browsers like Chrome or Edge.

For web developers, the days of supporting only a single browser are long behind us, but along with great advances in interoperability and tooling that enable us to more easily support multiple browsers, the number of permutations of browser versions, form factors, operating systems and screen resolutions are ever increasing. Understandably developers look for ways to simplify their approach. That might include recognising serious flaws in browsers and refusing to display content that we know probably won’t work, or at least put up an interstitial warning the user that their browser might not render the site correctly.

For IoT manufacturers, the responsibilities that come with putting a browser in your device may not be worth it. Is there really a sane use case for it? If so, how are you going to make sure it stays up to date? Maybe you could build in a “sunset” feature, which disables the browser if it does not receive an update for more than a year.

But I’m not convinced about what browsers in things actually achieve. We all carry around supercomputers in our pockets that have a browser and are always up to date. I’d like to see more products that integrate with them, and fewer that try to compete with them. IoT manufacturers should be leveraging technologies like bluetooth and other wireless standards, the physical web, and HTTP APIs. Allow other devices to talk to your product, focus on what your product is best at, and you can unlock the greatest value for your customers.